by Aaron Wentz

In light of recent events, this historical retrospective (originally published late in 2011 in an altered form here) remains relevant to our current moment. All sourcing (except for explicitly cited or hyperlinked material) comes from the archives at UND’s Special Collections.

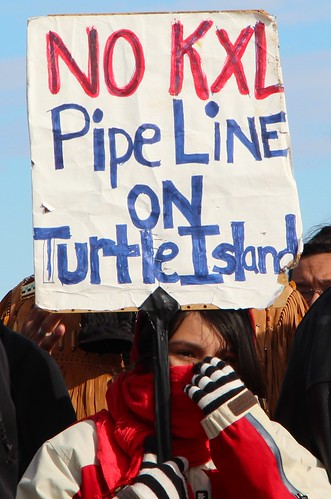

Recent events suggest that the final termination of the University of North Dakota’s Fighting Sioux nickname/logo is all but a formality. Given the current state of affairs regarding the status of UND’s Fighting Sioux nickname (the NCAA’s final decision to disallow use of the nickname/logo) and the impending special session of the ND legislature where it is widely expected that the recent legislation writing the continued use of the Fighting Sioux nickname/logo into state law will be repealed in light of the NCAA’s recent decision, it is instructive to look back at the history of the Fighting Sioux nickname/logo.

In the fall of 1930 it was suggested in a letter to the editor to the Dakota Student (UND’s student run newspaper, then and now) that the sports mascot ought to be changed from the Flickertail to the “Sioux” or “something Indian.” Further editorials (both from staff writers and letters to the editor) argued in favor of this change. A notable argument concerns retractors from the proposed nickname change, claiming that the tradition built around the use of the Flickertail mascot will be scrapped in favor of the new Sioux nickname. “Tradition, the desire to do as the fathers before you did, has long ago vanished from active effect. Why continue them any longer?” The day after the Sioux nickname was adopted as the school’s official mascot weeks later (Oct. 2, 1930), an editorial ran referring to the Sioux, historically, as “[the] most savage and bravest of Indians of the Northwest…[the] United States government was forced to send strong bodies of troops against them, and it was years before the braves of the Dakota territory were at last subdued.” Hence, the moniker confers such strength and fighting spirit upon the sports teams, the article suggests. What this account excludes is that the Indians referenced would not, in 1930, be allowed to attend UND until 1935.

In 1969, the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe formally granted UND the right to use the “Fighting Sioux” nickname during a ceremony wherein Sitting Bull’s grandson conferred the name “The Yankton Chief” onto then UND President George Starcher.

In February 1972, an incident involving ice sculptures built by UND fraternity members, which caricatured Indians engaging in cannibalism and sexually explicit behavior prompted Indian students and members of the American Indian Movement to attempt to physically dismantle the sculptures. A standoff with members of the fraternity ensued, which was eventually broken up by police. Later the same evening an Indian student attempted to dismantle similar sculptures at another UND fraternity. When members of the fraternity noticed what was happening, a number of them dragged the Indian student into their frat house, at which point the other Indian students rushed into the frat house to assist their comrade. In self-defense, the Indian student who was grabbed struck blows at the frat members. He was arrested and subsequently bailed out by then UND President Tom Clifford. Charges were later dropped. This incident prompted Indian group Time Out to recommend that UND drop the use of the Fighting Sioux nickname/logo.

In October 1992 Indian students were harassed at the homecoming parade. This incident sparked a movement to discontinue the use of nickname. A petition circulated which eventually collected 1,000 signatures and pushed then UND President Kendall Baker to look into changing the nickname. In response to the initial petition, a new petition began to circulate in support of the nickname. In 1993 Baker decided against retiring the nickname.

Over the next few years protests began to mount against the continued use of the nickname. Indian groups on campus began to publicly oppose the use of the nickname, national Indian groups, as well as the NAACP (among others). During this period UND made attempts to “promote awareness” about minority groups, as well as to offer revenues generated from the licensing of the “Fighting Sioux” nickname/logo to Indian groups on campus. These offers were declined.

In 1998, former UND goaltender Ralph Engelstad began the process of looking into building a new arena for the UND hockey team. His initial offer was to donate $50 million for a new arena and $50 million for the university. Concurrently, over the next two years, pressure was building to look seriously at changing the nickname. This pressure was spearheaded by the NCAA. Then UND President Kupchella established a taskforce to look into the viability of the nickname going forward. Concerns are raised about the effect such a decision would have on alumni donations. As the millennium was nearing, it became increasingly apparent that Kupchella was leaning toward changing the Nickname. Englestead proceeded to leverage the new arena against this possibility; he changed the terms of his offer, dumping the entire $100 million into construction of the new arena, leaving the University with no new endowment. Once construction is thoroughly underway, he publicly threatens to halt construction in the middle of winter and let the skeleton of the arena rot if the nickname is changed.

The State Board of Higher Education subsequently voted unanimously to continue using the nickname.

Construction finished on the new arena. As of 2001, Grand Forks is home to the finest hockey facility on the face of the earth. The next decade sees the death of Ralph Engelstad, the construction of the Betty Engelstad arena (adjacent to the Ralph), and continuing pressure from the NCAA to change the nickname. In 2007 UND settles a lawsuit with the NCAA, which precludes further litigation and guarantees the eventual retirement of the Fighting Sioux nickname unless support can be garnered from the state’s Indian tribes within three years. Coinciding with UND’s entrance into NCAA Division I status, and the tenuous nature of UND’s position, with the threat of losing its chance to join the Summit League and no agreement with the tribes, the ND State Board of Higher Education directs UND to retire the nickname.

In 2011, legislation passed in the ND legislature which essentially writes the continued use of the Fighting Sioux nickname into state law. After a confrontation with the NCAA in the Summer of 2011, it became clear that if UND is to continue on its present path in Division I sports, the nickname must go.

Which brings us to today. It is difficult to effectively eulogize a moniker which represents a tradition to which all sides lay claim. If nothing else, the history of the Fighting Sioux nickname is a history of public speech, a debate that, from its very outset was riddled with the ideological trappings of its time. As the decades passed and the pressure mounted, the shift from a break with the Flickertail tradition in the 1930’s to the establishment of a new tradition over the following 40 years, to the ensuing break with the Fighting Sioux tradition and all of the historical weight it bears, from the initial genocide of indigenous Indians, up through the establishment of Indian schools and the reservation system, the Fighting Sioux nickname became the placeholder for all of that history, the debate became the way to talk about that history, as well as the way to ignore it, on both sides.

Imagine taking a drive from the Ralph Engelstad Arena (REA) in Grand Forks, to the Spirit Lake reservation, roughly 100 miles away. If we were to place these two locations side by side and ask, “how are they related?” the answer we might come up with is that the marble floors of the crown jewel of the hockey world and the destitution (47% unemployment) and corruption of the Indian reservation are two sides of the same historical coin. We cannot have one without the other. The hard truth is that without the genocide that cleared the way for a series of reservations which bear a closer resemblance to Haiti than Hillsboro, ND, the ruthless modern productivity of post-war Capitalism which allowed such explosive development (affording such opulent construction) wouldn’t have been possible. Although his actions are worthy of scorn, Ralph Engelstad is hardly to blame, he just happened to be rich enough to wield political power brazenly. The way the REA is related to the Spirit Lake reservation is closer to the relationship between the REA and the cemetery it overlooks in Grand Forks. The reservations are the last vestige of a people decimated by a colonial genocide, bearing witness to the historical foundations of our current moment.

In 1862, an uprising sparked by broken treaties on the part of the US and concomitant famine led to the outbreak of the Dakota Wars, fought throughout Minnesota, including the Red River Valley, south of Fargo. After the US Army eventually put down the uprising and trials were held (some of which as short as five minutes), President Abraham Lincoln ordered the execution of thirty-eight men in the largest mass execution in US history. The subsequent internment and imprisonment of the Sioux population and later ordered killings (a bounty of $25 per scalp) of any Dakota (Sioux) found free within the boundaries of Minnesota fill in the missing of the historical image of the brave Sioux, hunted, and executed by US government sponsored gangs and vigilantes, referenced roughly seventy years later by the aforementioned Dakota Student columnist in defense of the Sioux nickname.

This history is incomplete and not intended to be exhaustive. It leaves out the ongoing struggles of the American Indian Movement, as well as other Indian organizations who fought against wave after wave of repression and violence and continue this fight today. It also leaves out a full account of Indian groups who supported and continue to support the Fighting Sioux Nickname. The goal of this account is not to reduce the history of the Nickname to a few moments of conflict and (many times cynical) bureaucratic decisions, but rather to establish that what’s at stake with the Nickname has never been merely a question of what’s embroidered on a jersey. The history of the Nickname is ultimately the history of how we choose to confront or ignore the history of our society, what the burden of that history effectively is, and what tradition, if any, we choose to maintain.

Aaron Wentz can be contacted at aaron.wentz@gmail.com

Recent Comments